web3 3️⃣

2021 brought a whole bunch of new vocabulary to describe the shifting technological landscape. We’ve tackled some of these in past editions. Think NFTs, the metaverse etc.

Web3 or Web 3.0 forms part of this new terminological landscape, yet it was coined by Ethereum co-founder Gavin Wood way back in 2014. To understand the proposition of Web3 it’s important to understand where we have come from in terms of Web1 and 2…

Web1 and Web2? 🤓

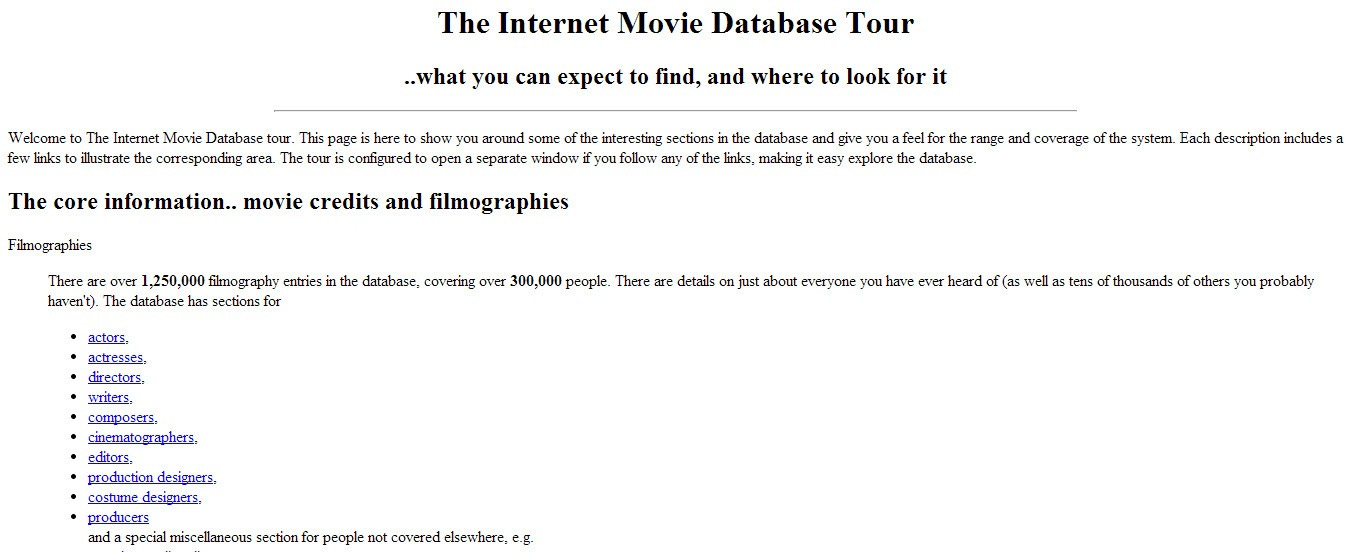

Web1 refers loosely to the period from inception of the web to the early 2000s. In Web1, web pages were largely “read only” and rendered static content. Most users were consumers who could look up an address on the world wide web and read its content. There was little or no interaction on the websites themselves.

Look at this slightly less eye-catching early version of IMDb hosted by Cardiff University in 1993.

Web2 changed this in the early 2000s onward. There was a sharp rise in interactive websites that were “read and write” and rendered dynamic content. Consumers could not only read information but also publish their own and expect the website to react to their actions taken.

Have a look at the interactive UI of Ribbet.

While Web2 provides us with amazing free services under centralised companies like Google and Amazon (to name a few) it often comes at the cost of privacy.

Web2 started collecting consumer data to plug into a recommender system in order to feed back more relevant content to consumers. The profit model that came out the other end was that companies like Google and Meta (formerly Facebook) monetised this data for advertising, building up buyer profiles for advertisers to target specific customers on these platforms.

So, what changes in Web3? 🧐

It’s hard to pin down exactly what Web3 is supposed to change, but the idea that consistently crops up is that Web3 should provide the same read and write as Web2 while incorporating ownership and verifiability.

In terms of ownership, rather than having big tech - Apple, Google etc. - controlling what happens on the internet, consumers can participate in the governance and operation of the internet protocols as shareholders, with the shares being in the form tokenised assets or cryptocurrencies.

In terms of verifiability, any promises between a platform and its end users can be “verified” to be true. For example, if a company promises to not store user metadata for marketing, this should be encoded and verifiable in a world running on Web3.

The critique 👀

Many prominent figures such as Jack Dorsey, Moxie Marlinspike and Elon Musk have expressed scepticism around Web3 technology.

The criticism all centres around the idea that there is a dissonance between the ideals of Web3 and the reality on the ground.

Ownership over blockchain ecosystems is far from equally distributed, as the majority ownership of cryptocurrencies is among first movers and some are even developed by private entities.

Moxie Marlinspike, cryptographer and creator of Signal, released a highly interesting blog post in which he attempts to write some functional decentralised apps (dApp) that run as one would expect in the Web3 paradigm.

One of his key takeaways from building Web3 applications was that the process still leaned on a few core services, replicating the centralisation we have today.

As of now Web3 is still struggling to find a firm footing in terms of what it is trying to be. It remains to be seen whether it can find lasting traction and utility, as baseless hype quickly loses steam.

claude

what’s a newspaper? 😕

Look, it’s no secret that consumer attention spans are a hot commodity. Not only are our attention spans waning over time, but there is an ongoing fight between social media platforms, streaming services (and everything in between) to capture our attention and retain it.

What do we actually consume? 🔎

If we were to simplify all of the digital media that we consume, it would look something like this:

📜 Text

🌆 Images

🎧 Audio

📺 Video

I think that we can agree that tech advancements, especially in the mobile space, have enabled more immersive and data-rich media consumption (audio and video) over time.

One only has to look as far as the explosive growth reported by the likes of TikTok, YouTube (video), and Spotify (audio) to understand how the modern day consumer prefers spending their time. Similarly, most of the other popular social media platforms have caught on too: Instagram created Reels; Twitter created Spaces, etc. And yes, I haven’t even begun to explore the metaverse, and how that’ll impact the way we consume media. 🤯

What does the future of text look like in the ever-changing digital world? Surprisingly, it’s not quite yet a relic of the past.

How do online publications make money? 🤓

Over the years, a number of physical publications failed to effectively digitise and disappeared. But those who pivoted online continue to fight the uphill battle to stay alive…

There are 2x common revenue models:

📊 Ads: these are the articles that you can read online for free, but only by scrolling through a page filled with display ads.

The goal of the publisher (i.e. Business Day) is to drive as much traffic to the article as possible, because they’re paid for each click that they can generate on ads on their website.

Google is often the intermediary between advertisers (i.e. Investec) and publishers (i.e. Business Day), and facilitates the transaction and ad placement (while taking a cut too).

⛔️ PayGates / subscriptions models: these are the articles that you click on, only to be told a paragraph in that the remainder of the article is reserved for premium (paying) members.

The goal of the publisher (i.e. News24) is to grow the number of paying subscribers while ensuring that the content is of good enough quality to ensure low churn.

This is often a riskier undertaking, as the cost to acquire new subscribers might outweigh the subscription fees being generated in the short-run.

So what’s the trend? 📈

Perhaps there’s no better case study than the NY Times – arguably the most esteemed newspaper in the world. The 170-year-old company has had its fair share of trial and error, yet has remained resolute in sticking to what it knows best.

Even though they have a dual revenue model, subscription revenue began exceeding ads revenue in 2020

They boasted 7.3M (+2.3M YoY) paying subscribers in 2020

And while their organic subscriber growth slowed down in 2021, they recently announced the acquisition of The Athletic for $550M, effectively adding +1.2M paying subscribers and 450 top tier sports journalists to their ecosystem 🤯.

All else equal, The NY Times is effectively buying 1.2M subscribers at ~$460 each - a number which will only turn profitable if every subscriber pays $2 a week (the current price on their website) for more than ~4.5 years.

One thing is for sure: the NY Times clearly backs its brand and value proposition to continue to grow its subscriber base while ensuring low churn.

Takeaways 🍔

Albeit much smaller relative to its data-rich competitors, there’s clearly still an addressable market for text-based (written) media. For the text-purists, there may be more light at the end of the tunnel: Along with the NY Times tale of expanding a subscriber base in a challenging digital world, platforms such as Substack (which we host our newsletter on) are growing in popularity.

But for the text-base publishers who don’t carry the same clout as the NY Times, perhaps there’s an opportunity to leapfrog image, audio and video and jump straight into the metaverse?

I’ll be watching (or reading) closely. 🍿

sash

matt loved this pod with sequoia’s roelof botha, which looked at his journey in vc and covers how sequoia are seeking to revolutionise the traditional vc fund model

thanks to some pressure from karl, sash finally started listening to the cold start problem audiobook